November 2, 2024

Underactuated Robotics or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Dynamics

Underactuated Robotics or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Dynamics

I was emailing back and forth with a professor in my engineering school when he sent me this ominous link: https://underactuated.csail.mit.edu/

I was taken to Russ Tedrake's grad level MIT course: Underactuated Robotics. I have been fascinated by the material since and I am documenting my learning as I wish to explore my own understanding of the material. I will introduce the topic and the fundamental ideas you need to get started with the course. I felt pretty good about the math level but there were a couple of concepts I was not familiar with so this may help if you are in the same position. I will likely update this blog post if I keep finidng relevant material.

Foreword:

Most of the material in this blog post (such as examples, pictures, etc.) is directly from Russ Tedrake's online notes and lecture videos. I have no idea what the copyright landscape looks like for this but the notes are published online, so I will assume I can safely republish my interpretations of the course material. Please send any Cease and Desist orders to my email.

There is something off about ASIMO:

Click here for the demo video

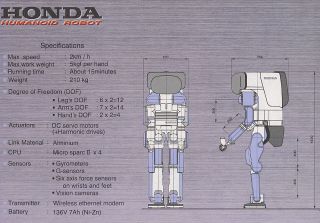

The robotics world was shocked when Honda announced they had been secretely developing a humanoid for the previous decade. They introduced their model, ASIMO, an astounding feat of engineering. ASIMO could walk, grip, avoid collisions, amongst other things.

But when we look at ASIMO's demo video, there is something wrong with its movement. Its just not natural. What is it that makes ASIMO's movement robotic, and Atlas' movement much more human-like?

Our underactuated world:

The fundamental reason comes down to dynamics. In order to achieve the desired control, ASIMO is essentially fighting a continous battle against its natural dynamics. Hence the bent knees and slow movements. The idea goes as follows: if we can use feedback to cancel the system's dynamics, the control problem is trivial. The idea has merit and is useful in various domains. Manipulator robots excel in the industrial setting where they are bolted down and dynamic cancellation is necessary. Full control all the time. Any desired acceleration can be achieved at any time.

Unfortunately, this control ideology begins to hold us down when we get to more complicated control models. I want to prove this to you. Stand up, and take three steps at your normal gait. Now turn around and take three really slow steps, kind of like ASIMO would. I am willing to bet you found the second go harder. Your body was expending much more energy fighting gravity and the movement was surely not too graceful. Although unnatural, the second type of movement is very well understood in control theory and is simple as long as you have enough power and have enough actuators to control your degrees of freedom. You are fully actuated.

The idea of exploiting mechanical systems and riding dynamics prevails in nature. An albatross can fly for kilometers without flapping its wings, a rainbow trout can ride up stream currents simply using their anatomical mechanisms, and a gymnast can do backflips with relative ease.

A trout swims upstream. The fish is dead and only tethered to position it correctly!

This type of control occurs when there are less actuators than degrees of freedom. This is known as underactuated control.

"If you had more research funding, would you be working with fully actuated robotics?" Prof. Manolis Kellis famously jokes with Tedrake in an MIT staff meeting.

Underactuated robotics does not come from a lack of materials (or research funding), it comes from a desire to maximize the control of our system at the trade-off of much more complicated control problem.

Now that we have an intuitive idea of underactuatuation, let us go into the math.

Prerequisite Skills:

Here is what I have found is necessary so far:

- All of calculus (up to vector / multivariable calculus)

- Differential Equations

- Linear Algebra

- Physics - Kinematics

- Patience - If you are an engineering undergrad like I am, this material will likely demand your full abilities but this stuff is really cool so stick with it

Fundamental Concepts:

I found that there were a couple of concepts that I had not been exposed to or used. In this blog post, I will walk you along the following funamental concepts that you need to get started:

- Generalized Coordinates

- Principle of Least Action (POLA)

- Lagrangian / Euler-Lagrange equation

- Control affine

- Robotic Manipulation Equation

- Underactuated vs. Fully-actuated mathematically

This should help make sense of the first lecture. I derived Lagrange and Euler-Lagrange in a slightly different way to Prof. Tedrake, however the math is equivalent (unless you catch an error, if so email me please).

Generalized Coordinates:

Generalized coordinates are parameters used to completely describe the configuration of a system. For our purposes, generalized coordinates might refer to the angles of each join in the robot. The main advantage of generalized coordinates is that they simplify system analysis. Rather than trying to keep track of the position and orientation of every component of the robot in three-dimensional space, you can instead use a smaller number of generalized coordinates that capture the essential degrees of freedom of the system. They are also quite nice because they align with Lagrangian mechanics which will be covered shortly.

Principle of Least Action:

POLA, A key concept in Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics, states that the path taken by a system between two states is the one for which the action is minimized. In other words, a ball thrown into the air follows a parabolic trajectory because any other path requires unnecessary work. Given the kinetic and potential energy of a robot (expressed in terms of the generalized coordinates and their time derivatives), you can apply the principle of least action and the Euler-Lagrange equation to derive the equations of motion.

Lagrangian / Euler-Lagrange Equation:

The Lagrangian will provide us a powerful alternative to Newton's laws which are in terms of forces. It can be very difficult, if not impossible to analyze all the forces in a complex system and the Lagrangian method gives us an elegant way to simplify things,

\ L = T - V\

where = kinetic energy and = potential energy.

We will then use the Euler-Lagrange equation to find the equations of motion of our system: = 0

where are our generalized coordinates.

Finding equations of motion of a double pendulum using Lagrangian and Euler-Lagrange equation:

This derivation is quite computationally heavy, but conceptually straightforward. Tedrake mentions using software to find the values but I found peace of mind in going through this derivation since I had never done Euler-Lagrange before. I will use software moving forward because 40 minutes for a derivation that can be done in milliseconds is unreasonable. I will not go through every step as that would be a LaTex nightmare but if you ever get stuck, follow along this video.

The location of and is denoted by and respectively. We simply use = . We could work in terms of but getting used to generalized coordinates cannot hurt.

:

=

:

= + =

We then take the time derivative of our positions in order to find our velocities, which we need for our kinetic energy:

:

=

:

=

We can rewrite our kinetic energy equation as

Reducing our and equations we get our final kinetic energy equation:

Finding the potential energy is trivial:

Now we plug and into our Lagrangian and we get:

Now we move onto Euler-Lagrange to find our motion equations and

Deriving the first term :

= 0

=

=

=

Deriving the second term :

= 0

=

=

=

Putting everything together, we get our equations of motion:

Robotic Manipulation Equation:

We can generalize most of our robots into this simple equation:

where:

- M is our generalized mass / inertia matrix

- C is our coriolis terms (or velocity product term) - when one joint is moving, it can induce forces on other joints that are also moving, due to the Coriolis and centrifugal effects

- g is our gravity term - this is assuming that our potential energy only comes from gravity; springs on our robot would throw this off

- B is our actuation matrix

- u is our torque control input

B will help us determine whether our system is underactuated or not

Control Affine:

A control affine system can be written in the following form:

- is the state of the system

- is the time derivative of the system

- is the control input - this is our actuation (servo torques, wheel's angular velocity, etc.)

- describes the uncontrolled dynamics - this is what happens when u = 0

- g(x) describes how the control input affects the system

We will see the control system The key characteristic of a control affine system is that the control input only multiplies the function and does not appear inside f or g, this gives us a linear part and a constant, making control affine systems easier to handle than more general nonlinear systems.

We will use the second-order system control in the form of:

where u is our control vector from earlier.

If there exists a u that achieves any desired acceleration , we call the system fully actuated. If we cannot, then the system is underactuated. In simpler terms, if we can perfectly control our system and not have to deal with dynamics, then our control problem is simple and fully actuated. If we cannot, then we must lean into the dynamics of our system, making the control problem more difficult but much more exciting.

Underactuated vs. Fully Actuated Mathematically:

An underactuated system has less actuators than degrees of freedom. Let us put the manipulator equation from earlier:

in terms of :

If B has full row rank, this indicates that the control inputs are able to influence the degrees of freedom independently, which indicates full actuation. If B does not have full row rank, it means that some control inputs will affect the motion in multiple degrees of freedom, indicating underactuation.

Conclusion:

I hope this blog post is a nice supplement to Tedrake's online lecture 1 and online textbook. This material reminds me of the Fantaisie Impromptu by Chopin. I knew it was somewhat above my skill level when I wanted to learn it but I am stubborn person and found it too beautiful to care. I had this feeling that if I kept banging my head against the wall for long enough, the wall would eventually give, and it did. I may never play like Daniil Trifonov but I properly learned the piece, and elevated my piano playing in the process. I hope my journey with underactuated robotics is similar. Do not hesitate to send me an email if you spot an error or have questions. Keep building.